what allowed the huguenots to worship freely in france

| French Wars of Faith | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the European wars of religion | ||||||||

St. Bartholomew's Day massacre by François Dubois | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

1595–1598: | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| Approximately 3,000,000 killed | ||||||||

The French Wars of Organized religion were a prolonged period of state of war and pop unrest between Catholics and Huguenots (Reformed/Calvinist Protestants) in the Kingdom of French republic between 1562 and 1598. Information technology is estimated that three one thousand thousand people perished in this menstruation from violence, dearth, or disease in what is considered the 2d deadliest religious state of war in European history (surpassed merely by the Thirty Years' State of war, which took eight million lives).[1]

Much of the conflict took place whilst Queen mother Catherine de' Medici, widow of Henry 2 of France, held significant political influence. It also involved a dynastic power struggle betwixt powerful noble families in the line for succession to the French throne: the wealthy, ambitious, and fervently Catholic ducal House of Guise (a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine, who claimed descent from Charlemagne) and their ally Anne de Montmorency, Lawman of French republic (i.e., commander in chief of the French military) versus the less wealthy House of Condé (a branch of the Business firm of Bourbon), princes of the blood in the line of succession to the throne who were sympathetic to Calvinism. Strange allies provided financing and other assist to both sides, with Habsburg Spain and the Duchy of Savoy supporting the Guises, and England supporting the Protestant side led by the Condés and by the Protestant Jeanne d'Albret, Queen of Navarre and wife of Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme and Male monarch of Navarre, and their son, Henry of Navarre.

Moderates, primarily associated with the French Valois monarchy and its advisers, tried to rest the state of affairs and avoid open mortality. This group, pejoratively known every bit Politiques, put their hopes in the ability of a stiff centralized authorities to maintain order and harmony. In contrast to the previous hardline policies of Henry Two and his father Francis I, they began introducing gradual concessions to Huguenots. A most notable moderate, at least initially, was the queen mother, Catherine de' Medici. Catherine, however, subsequently hardened her stance and, at the fourth dimension of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572, sided with the Guises. This pivotal historical event involved a complete breakdown of state control resulting in series of riots and massacres in which Catholic mobs killed between 5,000 and 30,000 Protestants over a period of weeks throughout the entire kingdom.

By the conclusion of the conflict in 1598, the Protestant Henry of Navarre, heir to the French throne, had converted to Catholicism and been crowned Henry IV of France. In that yr, he issued the Edict of Nantes, which granted Huguenots substantial rights and freedoms. His conversion did not terminate Catholic hostility towards Protestants or towards him personally, and he was eventually murdered past a Catholic extremist. The wars of religion threatened the authority of the monarchy, already frail nether the rule of Catherine's 3 sons and the final Valois kings: Francis 2, Charles Nine, and Henry 3. This changed under the reign of their Bourbon successor Henry 4. The Edict of Nantes was revoked later in 1685 with the Edict of Fontainebleau by Louis Xiv of French republic. Henry IV's governance and option of able administrators left a legacy of strong centralized authorities, stability, and relative economic prosperity.

Name and duration [edit]

Forth with French Wars of Religion and Huguenot Wars, the wars have likewise been variously described equally the "Viii Wars of Religion", or simply the "Wars of Religion" (only within France).

The exact number of wars and their respective dates are subject to continued contend by historians: some assert that the Edict of Nantes in 1598 ended the wars, while the ensuing resurgence of rebellious activity leads some to believe the Peace of Alès in 1629 is the actual conclusion. However, the agreed upon offset of the wars is the Massacre of Wassy in 1562, and the Edict of Nantes at least ended this series of conflicts. During this time, complex diplomatic negotiations and agreements of peace were followed by renewed conflict and ability struggles.

Background [edit]

Introduction of Reformation ideas [edit]

The Renaissance in France [edit]

Humanism, which began much before in Italy, arrived in France in the early sixteenth century, coinciding with the beginning of the French Protestant Reformation. The Italian revival of art and classical learning interested Francis I, who established imperial professorships in Paris, equipping more people with the cognition necessary to sympathise aboriginal literature. Francis I, however, had no quarrel with the established religious club and did not support reformation. Indeed, Pope Leo X, through the Concordat of Bologna increased the king's control over the French church building, granting him the power of nominating the clergy and levying taxes on church belongings. In France, dissimilar in Federal republic of germany, the nobles also supported the policies and the condition quo of their time.[ii]

The accent of Renaissance Humanism on advertising fontes, the return to the sources, had inevitably spread from the study and reconstruction of secular Greek and Latin texts, with a view to artistic and linguistic renewal, to the reading, study, and translation of the Church Fathers and finally the New Testament itself, with a view to religious renewal and reform.[3] Humanist scholars, who approached theology from a new critical and comparative perspective, argued that exegesis of Scripture must be based on an accurate understanding of the language(s) and grammar(s) used in writing the Greek scriptures (New Testament) and besides, later, the Hebrew Scriptures (Quondam Testament), rather than relying exclusively on the Vulgate, a Latin translation of the Bible, as in the Medieval period.[four]

In 1495 the Venetian Aldus Manutius began using the newly invented press press to produce small, inexpensive, pocket editions of Greek, Latin, and vernacular literature, making knowledge in all disciplines available for the first fourth dimension to a wide public.[5]

Press in mass editions (including cheap pamphlets and broadsides) allowed theological and religious ideas to be disseminated at an unprecedented pace. In 1519 John Froben, a humanist printer, published a collection of Luther'due south works. In one correspondence, he reported that 600 copies of such works were being shipped to French republic and Kingdom of spain and were sold in Paris.[6]

16th-century religious geopolitics on a map of modernistic France.

Controlled by Huguenot nobility

Contested between Huguenots and Catholics

Controlled past Catholic nobility

Lutheran-bulk surface area

The Meaux Circle was formed by a group of humanists including Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples and Guillaume Briçonnet, bishop of Meaux, in the attempt to reform preaching and religious life. The Meaux circle was joined by Vatable, a Hebraist,[7] and Guillaume Budé, the classicist and librarian to the king.[8] Lefèvre's works such as the Fivefold Psalter and his commentary on the Epistle to the Romans were humanist in approach. They put emphasis on the literal interpretation of Scripture and highlighted Christ. Lefèvre'south approach to the Scriptures influenced Luther'southward methodology on biblical interpretation.[6] Luther would later use his works in developing his lectures[9] that contained ideas that would spark the greater role of the Reformation known every bit Lutheranism. William Farel besides became part of the Meaux circumvolve. He was the leading minister of Geneva who invited John Calvin to serve there.[10] They were later on exiled out of Geneva because they opposed governmental intrusion upon church administration. Just their eventual render to Switzerland was followed by major developments in the Reformation that would later grow into Calvinism. Marguerite, Queen of Navarre, the sister of Male monarch Francis I and mother of Jeanne d'Albret, too became function of the circle.

Corruption of the established religious system [edit]

Corruption among the clergy showed the need for reform and Lutheran ideas made impressions of such hope.[eleven] Criticisms from the population played a part in spreading anticlerical sentiments, such as the publication of the Heptameron by Marguerite, a drove of stories that depicted immorality among the clergy.[12] Furthermore, the reduction of salvation to a business scheme based on the 'skilful works for sale' organisation added to the injury. Under these circumstances salvation by grace through faith in Jesus was a pleasant alternative (although Luther did teach baptismal regeneration). Works such every bit Farel'southward translation of the Lord'south Prayer, The True and Perfect Prayer, with Lutheran ideas became popular among the masses. It focused on the biblical footing of faith as a complimentary souvenir of God, conservancy by faith lone, and the importance of understanding in prayer. It likewise contained criticisms confronting the clergy of their fail that hampered growth of true religion.[12]

Growth of Calvinism [edit]

After an initial period of tolerance, Francis I began to take steps to repress the Protestant religions.

Protestant ideas were first introduced to France during the reign of Francis I of French republic (1515–1547) in the grade of Lutheranism, the teachings of Martin Luther. Discussion and written works circulated in Paris unimpeded for more than a year.[ when? ] Although Francis firmly opposed Lutheranism every bit being heresy, the initial difficulty was in recognizing precisely what was heretical and what was not. Roman Catholic doctrine and the definitions of its orthodox behavior were unclear.[13] Francis tried to steer a centre course in the developing religious schism in France.[fourteen] Despite this, in January 1535, Catholic government decided that those classified as "Lutherans" were actually Zwinglians (likewise heretical), followers of Huldrych Zwingli.[15] Calvinism, another form of Protestant religion, was soon introduced past John Calvin, a native of Noyon, Picardy,[16] who fled France in 1535 after the Thing of the Placards.[17]

Protestantism fabricated the most impact on French merchants and artists. Nevertheless, Calvinism appears to have developed with big support from the nobility. It is believed to have started with Louis Bourbon, Prince of Condé, who while returning home to French republic from a armed services campaign, passed through the Democracy of Geneva and heard a sermon by a Calvinist preacher.[xviii] Subsequently, Louis Bourbon would go a major effigy amongst the Huguenots of France. In 1560, Jeanne d'Albret, Queen regnant of Navarre, converted to Calvinism, maybe due to the influence of Theodore de Beze.[xviii] She later married Antoine de Bourbon, and both she and their son Henry of Navarre would be leaders amid the Huguenots.[19]

Affair of the Placards [edit]

Francis I of France had continued his policy of seeking a centre course in the religious rift in French republic until an incident called the Affair of the Placards.[14] The Thing of the Placards began in 1534, and started with protesters putting up anti-Cosmic posters. The posters were non Lutheran just were Zwinglian or "Sacramentarian" in the farthermost nature of the anti-Catholic content—specifically, the absolute rejection of the Catholic doctrine of "Real Presence."[14] Protestantism became identified as "a religion of rebels,"[ why? ] helping the Catholic Church to more easily ascertain Protestantism as heresy.

In the wake of the posters, the French monarchy took a harder stand up against the protesters.[15] [20] Francis had been severely criticized for his initial tolerance towards Protestants, and now was encouraged to repress them.[21] At the aforementioned fourth dimension, Francis was working on a policy of alliance with the Ottoman Empire.[22] The ambassadors in the 1534 Ottoman embassy to France accompanied Francis to Paris. They attended the execution by burning at the stake of those defenseless for the Affair of the Placards, on 21 January 1535, in front end of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris.[21]

John Calvin, a Frenchman, escaped from the persecution to Basle, Switzerland, where he published the Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1536.[14] In the same year, he visited Geneva, simply was forced out for trying to reform the church. When he returned past invitation in 1541, he wrote the Ecclesiastical ordinances, the constitution for a Genevan church, which was passed by the council of Geneva[ clarification needed ].

Massacre of Mérindol [edit]

The Massacre of Mérindol took place in 1545 when Francis I of French republic ordered the penalty of the Waldensians of the village of Mérindol. The Waldensians had recently affiliated with the Reformed tradition of Protestantism, participating in "dissident religious activities". Historians estimate that Provençal troops killed hundreds to thousands of residents there and in the 22 to 28 nearby villages they destroyed. They captured hundreds of men and sent them to labor in the French galleys.[23]

Francis I died on 31 March 1547 and was succeeded to the throne by his son Henry Two, who continued the harsh religious policy that his begetter had followed during the last years of his reign. Indeed, Henry II was fifty-fifty more than astringent against the Protestants than Francis I had been. Henry 2 sincerely believed that the Protestants were heretics. On 27 June 1551, Henry II issued the Edict of Châteaubriant, which sharply concise Protestant rights to worship, gather, or even to hash out faith at work, in the fields, or over a repast.

In the 1550s, the institution of the Geneva church building provided leadership to the disorganized French Calvinist (Huguenot) church.[24] The French intensified the fight against heresy in the 1540s forcing Protestants to gather secretly to worship.[25] Merely by the eye of the century, the adherents to Protestantism in French republic had increased markedly in number and ability, as the nobility in particular converted to Calvinism. Historians guess that in the 1560s more than half of the nobility were Calvinist (or Huguenot), and ane,200–1,250 Calvinist churches had been established; past the outbreak of war in 1562, there were perhaps ii one thousand thousand Calvinists in France. The conversion of the nobility constituted a substantial threat to the monarchy.[26] Calvinism proved attractive to people from across the social hierarchy and occupational divides, and it was highly regionalized, with no coherent pattern of geographical spread.

Rise of factionism [edit]

The adventitious death of Henry Ii in 1559 created a political vacuum that encouraged the rise of factions, eager to grasp power. Francis Ii of France, at this signal only 15 years former, was weak and lacked the qualities that allowed his predecessors to impose their will on the leading noblemen at court. However, the Firm of Guise, having an advantage in the Rex's wife, Mary, Queen of Scots, who was their niece, moved chop-chop to exploit the situation at the expense of their rivals, the House of Montmorency.[27] [28] Within days of the King's accession, the English ambassador reported that "the business firm of Guise ruleth and doth all about the French King".[29]

The "Amboise conspiracy," or "Tumult of Amboise" [edit]

On 10 March 1560, a group of disaffected nobles (led by Jean du Barry, seigneur de la Renaudie) attempted to housebreak the young Francis Two and eliminate the Guise faction.[xxx] Their plans were discovered before they could succeed, and the government executed hundreds of suspected plotters.[31] The Guise brothers suspected Louis I de Bourbon, prince de Condé, of leading the plot.[30] He was arrested and due to be executed before existence freed in the political anarchy that followed the sudden death of Francis II, adding to the tensions of the menses.[32] (In the polemics that followed, the term "Huguenot" for France's Protestants came into widespread usage.[33])

Iconoclasm and civic disturbances [edit]

The first instances of Protestant iconoclasm, the devastation of images and statues in Catholic churches, occurred in Rouen and La Rochelle in 1560. The following year, mobs carried out iconoclasm in more than 20 cities and towns; Cosmic urban groups attacked Protestants in bloody reprisals in Sens, Cahors, Carcassonne, Tours and other cities.[34]

Death of Francis II [edit]

![]()

On 5 Dec 1560, Francis II died, and his female parent Catherine de' Medici became regent for her second son, Charles Nine.[35] Inexperienced and faced with the legacy of debt from the Habsburg–Valois conflict, Catherine felt that she had to steer the throne advisedly between the powerful and conflicting interests that surrounded information technology, embodied by the powerful aristocrats who led substantially private armies. She was intent on preserving the independence of the throne.[36] She was prepared to bargain favourably with the House of Bourbon in lodge to have a counterweight against the overmighty Guise, arranging a deal with Antoine of Navarre in which he would renounce the rights to the regency in return for the freedom of Condé and the position of lieutenant full general of the kingdom.[37] Although she was a sincere Roman Catholic, she nominated a moderate chancellor, Michel de l'Hôpital, who urged a number of measures providing for borough peace so that a religious resolution could be sought past a sacred council.[38] [39]

Colloquy of Poissy and the Edict of Saint-Germain [edit]

The Regent Queen-Mother Catherine de Medici had three courses of action open to her in solving the religious crisis in France. Get-go she might revert to persecution of the Huguenots. This, notwithstanding, had been tried and had failed—witness the fact that the Huguenots were now more numerous than they had e'er been earlier.[40] Secondly, Catherine could win over the Huguenots. This though might atomic number 82 direct to ceremonious state of war.[40] Thirdly, Catherine might endeavor to heal the religious division in the country by ways of a national council or colloquy on the topic.[40] Catherine chose the third course to pursue. Thus, a national council of clergy gathered on the banks of the Seine River in the town of Poissy in July 1561. The quango had been formed in 1560 during the Estates-General of Saint-Germain-en-Laye when the council of prelates accepted the crown's request to give Huguenots a hearing. The Protestants were represented by 12 ministers and xx laymen, led past Théodore de Bèze. Neither grouping sought toleration of Protestants, but wanted to achieve some course of hold for the basis of a new unity. The council debated the religious upshot at Poissy all summertime. Meanwhile, a coming together betwixt Bèze and the Cardinal of Lorraine, of the Firm of Guise, seemed promising; both appeared set to compromise on the class of worship. The King of Navarre and the Prince of Condé petitioned the Regent for the young King Charles Nine—the Queen-Mother, Catherine de Medici for the complimentary practise of religion.[41] In July 1561, the Parliament passed and the Regent signed the Edict of July which recognised Roman Catholicism as the state religion simply forbade any and all "injuries or injustices" against the citizens of France on the ground of religion.[42] However, despite this measure, by the end of the Colloquy in Poissy in Oct 1561, it was articulate that the divide between Catholic and Protestant ideas was already too broad.[43]

In early 1562, the regency regime attempted to quell escalating disorder in the provinces, which had been encouraged by factional feuds at court, by instituting the Edict of Saint-Germain, also known as the Edict of Jan. The legislation made concessions to the Huguenots to dissuade them from rebelling. It immune them to worship publicly outside of towns and privately inside them. On i March, still, a faction of the Guise family's retainers attacked a Calvinist service in Wassy-sur-Blaise in Champagne, massacring the worshippers and well-nigh of the residents of the boondocks. The Huguenot Jean de la Fontaine described the events:

"The Protestants were engaged in prayer exterior the walls, in conformity with the king's edict, when the Duke of Guise approached. Some of his suite insulted the worshippers, and from insults they proceeded to blows, and the Duke himself was accidentally wounded in the cheek. The sight of his blood enraged his followers, and a full general massacre of the inhabitants of Vassy ensued."[44]

1562–1570 [edit]

The "get-go" war (1562–1563) [edit]

Massacre de Vassy in 1562, print by Hogenberg, end of 16th century

Looting of the Churches of Lyon by the Calvinists, in 1562, Antoine Carot

The massacre of Vassy, on 1 March 1562, provoked open up hostilities between the factions supporting the two religions.[45] A group of Protestant nobles, led past the prince of Condé and proclaiming that they were liberating the king and regent from "evil" councillors, organised a kind of protectorate over the Protestant churches. On two Apr 1562, Condé and his Protestant followers seized the urban center of Orléans.[46] Their example was soon followed by Protestant groups effectually France. Protestants seized and garrisoned the strategic towns of Angers, Blois, and Tours along the Loire River.[46] In the Rhône River valley, Protestants nether François de Beaumont, businesswoman des Adrets, attacked Valence; in this attack Guise's lieutenant was killed.[46] Later, the Protestants captured Lyon in 29–thirty April[46] [47] and proceeded to demolish all Catholic institutions in the city.[47]

Although the Huguenots had begun to mobilise for state of war before Vassy,[48] Condé used the massacre of Vassy as evidence that the July Edict of 1561 had been broken, lending further weight to his campaign. Hoping to turn over the metropolis to Condé, the Huguenots of Toulouse seized the Hôtel de ville but were countered past aroused Catholic mobs resulting in street battles and the killing of around 3,000—more often than not Huguenots—during the 1562 Riots of Toulouse. Additionally, on 12 April 1562, and later in July, there were massacres of Huguenots at Sens and at Tours, respectively.[46] Every bit conflicts connected and open hostilities broke out, the Crown revoked the Edict under pressure from the Guise faction.

The major engagements of the state of war occurred at Rouen, Dreux, and Orléans. At the Siege of Rouen (May–October 1562), the crown regained the city, merely Antoine of Navarre died of his wounds.[49] In the Battle of Dreux (December 1562), Condé was captured by the Guises, and Montmorency, the governor general, was captured past those opposing the crown. In February 1563, at the Siege of Orléans, Francis, Knuckles of Guise, was shot and killed by the Huguenot Jean de Poltrot de Méré. As he was killed exterior of directly combat, the Guise considered this an assassination on the orders of the duke's enemy, Admiral Coligny. The pop unrest caused by the bump-off, coupled with the resistance past the city of Orléans to the siege, led Catherine de' Medici to mediate a truce, resulting in the Edict of Amboise on 19 March 1563.[l]

The "Armed Peace" (1563–1567) and the "2d" war (1567–1568) [edit]

Print depicting Huguenot assailment against Catholics at sea, Horribles cruautés des Huguenots, 16th century

Plate from Richard Rowlands, Theatrum Crudelitatum haereticorum nostri temporis (1587), depicting supposed Huguenot atrocities

The Edict of Amboise was generally regarded as unsatisfactory by all concerned, and the Guise faction was specially opposed to what they saw as unsafe concessions to heretics. The crown tried to re-unite the two factions in its efforts to re-capture Le Havre, which had been occupied by the English in 1562 as office of the Treaty of Hampton Courtroom between its Huguenot leaders and Elizabeth I of England. That July, the French expelled the English. On 17 Baronial 1563, Charles 9 was declared of historic period at the Parlement of Rouen ending the regency of Catherine de Medici.[51] His female parent continued to play a principal role in politics, and she joined her son on a Grand Tour of the kingdom between 1564 and 1566, designed to reinstate crown authority. During this time, Jeanne d'Albret met and held talks with Catherine at Mâcon and Nérac.

Reports of iconoclasm in Flanders led Charles Nine to lend support to the Catholics there; French Huguenots feared a Cosmic re-mobilisation against them. Philip II of Kingdom of spain'southward reinforcement of the strategic corridor from Italy north forth the Rhine added to these fears, and political discontent grew. After Protestant troops unsuccessfully tried to capture and have control of King Charles Ix in the Surprise of Meaux, a number of cities, such as La Rochelle, declared themselves for the Huguenot crusade. Protesters attacked and massacred Catholic laymen and clergy the post-obit mean solar day in Nîmes, in what became known equally the Michelade.

This provoked the 2d State of war and its main military engagement, the Battle of Saint-Denis, where the crown'southward commander-in-chief and lieutenant general, the 74-year-old Anne de Montmorency, died. The war was brief, ending in another truce, the Peace of Longjumeau (March 1568),[52] which was a reiteration of the Peace of Amboise of 1563 and once once again granted pregnant religious freedoms and privileges to Protestants.[52]

The "third" war (1568–1570) [edit]

In reaction to the Peace, Catholic confraternities and leagues sprang up across the state in defiance of the law throughout the summer of 1568. Huguenot leaders such as Condé and Coligny fled court in fear for their lives, many of their followers were murdered, and in September, the Edict of Saint-Maur revoked the freedom of Huguenots to worship. In November, William of Orange led an army into France to support his swain Protestants, merely, the army being poorly paid, he accustomed the crown's offer of money and gratuitous passage to exit the country.

The Huguenots gathered a formidable army under the command of Condé, aided by forces from southward-eastward France, led past Paul de Mouvans, and a contingent of fellow Protestant militias from Germany — including fourteen,000 mercenary reiters led by the Calvinist Knuckles of Zweibrücken.[53] After the Duke was killed in action, his troops remained nether the employ of the Huguenots who had raised a loan from England against the security of the Jeanne d'Albret's crown jewels.[54] Much of the Huguenots' financing came from Queen Elizabeth of England, who was likely influenced in the matter by Sir Francis Walsingham.[53] The Catholics were commanded past the Duke d'Anjou—after Rex Henry III—and assisted by troops from Spain, the Papal States, and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.[55]

The Protestant regular army laid siege to several cities in the Poitou and Saintonge regions (to protect La Rochelle), and and so Angoulême and Cognac. At the Battle of Jarnac (xvi March 1569), the prince of Condé was killed, forcing Admiral de Coligny to take control of the Protestant forces, nominally on behalf of Condé'south 15-yr-sometime son, Henry, and the 16-yr-old Henry of Navarre, who were presented by Jeanne d'Albret equally the legitimate leaders of the Huguenot crusade against royal say-so. The Battle of La Roche-l'Abeille was a nominal victory for the Huguenots, but they were unable to seize control of Poitiers and were soundly defeated at the Battle of Moncontour (30 Oct 1569). Coligny and his troops retreated to the south-w and regrouped with Gabriel, comte de Montgomery, and in spring of 1570, they pillaged Toulouse, cut a path through the due south of France, and went upwards the Rhone valley up to La Charité-sur-Loire.[56] The staggering regal debt and Charles Nine'due south desire to seek a peaceful solution[57] led to the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (8 Baronial 1570), negotiated by Jeanne d'Albret, which over again allowed some concessions to the Huguenots.

St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre and after (1572–1573) [edit]

Anti-Protestant massacres of Huguenots at the hands of Catholic mobs continued, in cities such as Rouen, Orangish, and Paris. Matters at Court were complicated as Male monarch Charles IX openly centrolineal with the Huguenot leaders — especially Admiral Gaspard de Coligny. Meanwhile, the Queen Mother became increasingly fearful of the unchecked ability wielded by Coligny and his supporters, especially as it became clear that Coligny was pursuing an alliance with England and the Dutch Protestant rebels.

Coligny, along with many other Calvinist nobles, arrived in Paris for the wedding of the Cosmic princess Margaret of France to the Protestant prince Henry of Navarre on 18 August 1572. On 22 August, an assassin made a failed attempt on Coligny's life, shooting him in the street from a window. While historians have suggested Charles de Louvier, sieur de Maurevert, equally the likely assailant, historians have never determined the source of the order to kill Coligny (it is improbable that the order came from Catherine).[58]

In preparation for her son'due south wedding, Jeanne d'Albret had arrived in Paris, where she went on daily shopping trips. She died there on ix June 1572, and for centuries afterward her death, Huguenot writers accused Catherine de' Medici of poisoning her.

Amidst fears of Huguenot reprisals for the murder, the Knuckles of Guise and his supporters acted. In the early forenoon of 24 August, they killed Coligny in his lodgings with several of his men. Coligny's body was thrown from the window into the street, and was subsequently mutilated, castrated, dragged through the mud, thrown in the river, suspended on a gallows, and burned by the Parisian crowd.[59]

This assassination began the series of events known equally the St. Bartholomew'southward Mean solar day massacre. For the side by side v days, the city erupted as Catholics massacred Calvinist men, women, and children and looted their houses.[60] Male monarch Charles IX appear that he had ordered the massacre to prevent a Huguenot insurrection and proclaimed a twenty-four hours of jubilee in celebration even as the killings continued.[61] Over the next few weeks, the disorder spread to more than a dozen cities across France. Historians approximate that 2,000 Huguenots were killed in Paris and thousands more in the provinces; in all, maybe 10,000 people were killed.[62] Henry of Navarre and his cousin, the young Prince of Condé, managed to avoid expiry by agreeing to convert to Catholicism. Both repudiated their conversions afterwards they escaped Paris.

The massacre provoked horror and outrage amongst Protestants throughout Europe, simply both Philip 2 of Kingdom of spain and Pope Gregory Xiii, following the official version that a Huguenot coup had been thwarted, celebrated the result. In France, Huguenot opposition to the crown was seriously weakened by the deaths of many of the leaders. Many Huguenots emigrated to Protestant countries. Others reconverted to Catholicism for survival, and the remainder concentrated in a small number of cities where they formed a majority.

The "fourth" war (1572–1573) [edit]

The massacres provoked further military machine action, which included Cosmic sieges of the cities of Sommières (past troops led by Henri I de Montmorency), Sancerre, and La Rochelle (past troops led by the duke of Anjou). The cease of hostilities was brought on by the election (xi–fifteen May 1573) of the Duke of Anjou to the throne of Poland and by the Edict of Boulogne (signed in July 1573), which severely curtailed many of the rights previously granted to French Protestants. Based on the terms of the treaty, all Huguenots were granted immunity for their past deportment and the liberty of belief. Notwithstanding, they were permitted the liberty to worship only inside the three towns of La Rochelle, Montauban, and Nîmes, and even then merely inside their own residences. Protestant aristocrats with the correct of loftier-justice were permitted to celebrate marriages and baptisms, but only before an assembly limited to ten persons outside of their family.[63]

1574–1584 [edit]

Death of Charles 9 and the "5th" state of war (1574–1576) [edit]

In the absenteeism of the duke of Anjou, disputes between Charles and his youngest brother, the duke of Alençon, led to many Huguenots congregating around Alençon for patronage and support. A failed coup at Saint-Germain (February 1574), allegedly aiming to release Condé and Navarre who had been held at courtroom since St Bartholemew's, coincided with rather successful Huguenot uprisings in other parts of France such every bit Lower Normandy, Poitou, and the Rhône valley, which reinitiated hostilities.[64]

Three months after Henry of Anjou's coronation as Rex of Poland, his brother Charles Ix died (May 1574) and his mother declared herself regent until his return. Henry secretly left Poland and returned via Venice to France, where he faced the defection of Montmorency-Damville, ex-commander in the Midi (Nov 1574). Despite having failed to take established his dominance over the Midi, he was crowned King Henry III, at Rheims (February 1575), marrying Louise Vaudémont, a kinswoman of the Guise, the following solar day. Past April, the crown was already seeking to negotiate,[65] and the escape of Alençon from courtroom in September prompted the possibility of an overwhelming coalition of forces against the crown, as John Casimir of the Palatinate invaded Champagne. The crown hastily negotiated a truce of seven months with Alençon and promised Casimir's forces 500,000 livres to stay east of the Rhine,[66] but neither action secured a peace. By May 1576, the crown was forced to accept the terms of Alençon, and the Huguenots who supported him, in the Edict of Beaulieu, known every bit the Peace of Monsieur.

The Cosmic League and the "sixth" war (1576–1577) [edit]

The Edict of Beaulieu granted many concessions to the Calvinists, but these were brusk-lived in the face of the Cosmic League – which the ultra-Catholic, Henry I, Knuckles of Guise, had formed in opposition to it. The House of Guise had long been identified with the defence force of the Roman Catholic Church and the Duke of Guise and his relations – the Duke of Mayenne, Duke of Aumale, Duke of Elboeuf, Duke of Mercœur, and the Duke of Lorraine – controlled extensive territories that were loyal to the League. The League also had a big post-obit among the urban centre class. The Estates-Full general of Blois (1576) failed to resolve matters, and by December, the Huguenots had already taken upwardly arms in Poitou and Guyenne. While the Guise faction had the unwavering support of the Spanish Crown, the Huguenots had the advantage of a stiff ability base in the southwest; they were too discreetly supported by foreign Protestant governments, but in practice, England or the German states could provide few troops in the ensuing conflict. After much posturing and negotiations, Henry III rescinded virtually of the concessions that had been fabricated to the Protestants in the Edict of Beaulieu with the Treaty of Bergerac (September 1577), confirmed in the Edict of Poitiers passed half-dozen days later.[67]

The "seventh" state of war (1579–1580) and the death of Anjou (1584) [edit]

Despite Henry according his youngest brother Francis the championship of Knuckles of Anjou, the prince and his followers connected to create disorder at courtroom through their involvement in the Dutch Revolt. Meanwhile, the regional situation disintegrated into disorder as both Catholics and Protestants armed themselves in 'cocky defence'. In Nov 1579, Condé seized the town of La Fère, leading to another circular of military action, which was brought to an end by the Treaty of Fleix (November 1580), negotiated by Anjou.

The fragile compromise came to an end in 1584, when the Duke of Anjou, the King'south youngest blood brother and heir presumptive, died. As Henry III had no son, under Salic Law, the next heir to the throne was the Calvinist Prince Henry of Navarre, a descendant of Louis Ix whom Pope Sixtus V had excommunicated along with his cousin, Henri Prince de Condé. When information technology became clear that Henry of Navarre would not renounce his Protestantism, the Duke of Guise signed the Treaty of Joinville (31 December 1584) on behalf of the League, with Philip Ii of Espana, who supplied a considerable annual grant to the League over the post-obit decade to maintain the civil war in France, with the hope of destroying the French Calvinists. Nether pressure from the Guise, Henry Three reluctantly issued the Treaty of Nemours (July) and an edict suppressing Protestantism and annulling Henry of Navarre's right to the throne.

War of the Iii Henrys (1587–1589) [edit]

The succession crunch [edit]

King Henry Three at first tried to co-opt the head of the Catholic League and steer it towards a negotiated settlement.[68] This was anathema to the Guise leaders, who wanted to bankrupt the Huguenots and divide their considerable assets with the King. A exam of Male monarch Henry Three'southward leadership occurred at the coming together of the Estates-Full general at Blois in December 1576.[68] At the coming together of the Estates-Full general, in that location was only one Huguenot delegate nowadays amongst all of the three estates;[68] the balance of the delegates were Catholics with the Cosmic League heavily represented. Accordingly, the Estates-General pressured Henry Iii into conducting a war against the Huguenots. In response Henry said he would reopen hostilities with the Huguenots but wanted the Estates-Full general to vote him the funds to acquit out the state of war.[68] Yet, the Tertiary Manor refused to vote for the necessary taxes to fund this war.

The state of affairs degenerated into open up warfare even without the King having the necessary funds. Henry of Navarre again sought foreign assistance from the German princes and Elizabeth I of England. Meanwhile, the solidly Catholic people of Paris, nether the influence of the Committee of 16, were becoming dissatisfied with Henry Iii and his failure to defeat the Calvinists. On 12 May 1588, the Twenty-four hour period of the Barricades, a pop insurgence raised barricades on the streets of Paris to defend the Knuckles of Guise against the alleged hostility of the king, and Henry III fled the city. The Committee of 16 took complete control of the regime, while the Guise protected the surrounding supply lines. The arbitration of Catherine de'Medici led to the Edict of Spousal relationship, in which the crown accepted about all the League's demands: reaffirming the Treaty of Nemours, recognizing Cardinal de Bourbon equally heir, and making Henry of Guise Lieutenant-General.

The Estates-Full general of Blois and bump-off of Henry of Guise (1588) [edit]

Refusing to return to Paris, Henry 3 called for an Estates-Full general at Blois in September 1588.[69] During the Estates-General, Henry Three suspected that the members of the third estate were being manipulated past the League and became convinced that Guise had encouraged the duke of Savoy'south invasion of Saluzzo in Oct 1588. Viewing the House of Guise equally a dangerous threat to the ability of the Crown, Henry Iii decided to strike first. On 23 Dec 1588, at the Château de Blois, Henry of Guise and his brother, the Cardinal de Guise, were lured into a trap by the King's guards.[70] The Duke arrived in the quango bedchamber where his blood brother the Cardinal waited. The Duke was told that the King wished to see him in the private room adjoining the royal chambers. There guardsmen seized the duke and stabbed him in the heart, while others arrested the Central who later died on the pikes of his escort. To brand certain that no contender for the French throne was free to act confronting him, the King had the Duke's son imprisoned. The Duke of Guise had been highly popular in France, and the Catholic League alleged open war against Male monarch Henry III. The Parlement of Paris instituted criminal charges against the Male monarch, who now joined forces with his cousin, the Huguenot, Henry of Navarre, to war confronting the League.

The bump-off of Henry III (1589) [edit]

It thus fell upon the younger brother of the Duke of Guise, the Duke of Mayenne, to lead the Catholic League. The League presses began printing anti-royalist tracts under a variety of pseudonyms, while the Sorbonne proclaimed on seven January 1589, that it was just and necessary to depose Henry Iii, and that any private denizen was morally complimentary to commit regicide.[seventy] In July 1589, in the majestic camp at Saint-Cloud, a Dominican friar named Jacques Clément gained an audience with the King and drove a long pocketknife into his spleen. Clément was killed on the spot, taking with him the information of who, if anyone, had hired him. On his deathbed, Henry Three called for Henry of Navarre, and begged him, in the name of statecraft, to become a Cosmic, citing the brutal warfare that would ensue if he refused.[71] In keeping with Salic Law, he named Henry every bit his heir.

Henry Iv's "Conquest of the Kingdom" (1589–1593) [edit]

The situation in 1589 was that Henry of Navarre, now Henry IV of French republic, held the due south and w, and the Cosmic League the north and east. The leadership of the Catholic League had devolved to the Duke de Mayenne, who was appointed Lieutenant-General of the kingdom. He and his troops controlled most of rural Normandy. Notwithstanding, in September 1589, Henry inflicted a astringent defeat on the Knuckles at the Battle of Arques. Henry'southward army swept through Normandy, taking town subsequently town throughout the winter.

The Rex knew that he had to take Paris if he stood any chance of ruling all of French republic. This, however, was no easy task. The Cosmic League'southward presses and supporters connected to spread stories well-nigh atrocities committed against Catholic priests and the laity in Protestant England (see Forty Martyrs of England and Wales). The city prepared to fight to the death rather than take a Calvinist rex.

The Battle of Ivry, fought on 14 March 1590, was another decisive victory for Henry confronting forces led past the Duke of Mayenne. Henry's forces then went on to besiege Paris, simply after a long and desperately fought resistance by the Parisians, Henry'southward siege was lifted by a Castilian army under the command of the Duke of Parma. Then, what had happened at Paris was repeated at Rouen (November 1591 – March 1592).

Parma was subsequently wounded in the mitt during the Siege of Caudebec whilst trapped by Henry's ground forces. Having and then made a miraculous escape from there, he withdrew into Flanders, but with his health speedily declining, Farnese called his son Ranuccio to control his troops. He was, nonetheless, removed from the position of governor by the Spanish courtroom and died in Arras on 3 December. For Henry and the Protestant army at least, Parma was no longer a threat.

State of war in Brittany [edit]

Meanwhile, Philippe Emmanuel, Duke of Mercœur, whom Henry Iii had fabricated governor of Brittany in 1582, was endeavouring to make himself independent in that province. A leader of the Catholic League, he invoked the hereditary rights of his wife, Marie de Luxembourg, who was a descendant of the dukes of Brittany and heiress of the Blois-Brosse claim to the duchy every bit well as Duchess of Penthièvre in Brittany, and organized a government at Nantes. Proclaiming his son "prince and duke of Brittany", he allied with Philip Two of Spain, who sought to identify his own daughter, infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia, on the throne of Brittany. With the help of the Castilian nether Juan del Águila, Mercœur defeated Henry IV's forces nether the Duke of Montpensier at the Battle of Craon in 1592, but the royal troops, reinforced by English contingents, presently recovered the advantage; in September 1594, Martin Frobisher and John Norris with eight warships and 4,000 men besieged Fort Crozon near Brest and captured it on November 7, killing 350 Spaniards as simply 13 survived.

Toward peace (1593–1598) [edit]

Conversion [edit]

Archway of Henry Iv in Paris, 22 March 1594, with 1,500 cuirassiers.

Departure of Spanish troops from Paris, 22 March 1594.

Despite the campaigns between 1590 and 1592, Henry 4 was "no closer to capturing Paris".[72] Realising that Henry III had been right and that there was no prospect of a Protestant king succeeding in resolutely Catholic Paris, Henry agreed to catechumen, reputedly stating "Paris vaut bien une messe" ("Paris is well worth a Mass"). He was formally received into the Cosmic Church in 1593, and was crowned at Chartres in 1594 every bit League members maintained command of the Cathedral of Reims, and, sceptical of Henry'south sincerity, continued to oppose him. He was finally received into Paris in March 1594, and 120 League members in the metropolis who refused to submit were banished from the capital.[73] Paris' capitulation encouraged the same of many other towns, while others returned to back up the crown after Pope Clement Eight absolved Henry, revoking his excommunication in render for the publishing of the Tridentine Decrees, the restoration of Catholicism in Béarn, and appointing simply Catholics to high office.[73] Evidently Henry's conversion worried Protestant nobles, many of whom had, until and so, hoped to win not just concessions but a consummate reformation of the French Church, and their acceptance of Henry was by no means a foregone determination.

State of war with Spain (1595–1598) [edit]

By the end of 1594, certain League members still worked against Henry across the country, only all relied on Spain'southward support. In January 1595, the king declared war on Spain to evidence Catholics that Spain was using faith equally a comprehend for an attack on the French state—and to show Protestants that his conversion had not made him a puppet of Kingdom of spain. Also, he hoped to reconquer large parts of northern France from the Franco-Spanish Catholic forces.[74] The conflict mostly consisted of military action aimed at League members, such as the Battle of Fontaine-Française, though the Castilian launched a concerted offensive in 1595, taking Le Catelet, Doullens and Cambrai (the latter after a trigger-happy bombardment), and in the jump of 1596 capturing Calais by Apr. Following the Spanish capture of Amiens in March 1597 the French crown laid siege until its surrender in September. With that victory Henry's concerns and so turned to the situation in Brittany where he promulgated the Edict of Nantes and sent Bellièvre and Brulart de Sillery to negotiate a peace with Spain. The war was drawn to an official close after the Edict of Nantes, with the Peace of Vervins in May 1598.

Resolution of the War in Brittany (1598–1599) [edit]

In early 1598, the king marched confronting Mercœur in person, and received his submission at Angers on xx March 1598. Mercœur afterwards went to exile in Hungary. Mercœur'southward girl and heiress was married to the Duke of Vendôme, an illegitimate son of Henry 4.

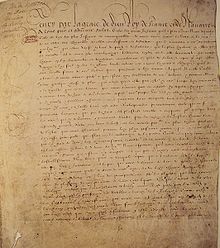

The Edict of Nantes (1598) [edit]

Henry IV was faced with the chore of rebuilding a shattered and impoverished kingdom and uniting it under a unmarried authorisation. Henry and his advisor, the Duke of Sully saw that the essential starting time step in this was the negotiation of the Edict of Nantes, which to promote civil unity granted the Huguenots substantial rights—but rather than being a sign of 18-carat toleration, was in fact a kind of grudging truce between the religions, with guarantees for both sides.[75] The Edict can be said to mark the cease of the Wars of Religion, though its apparent success was not assured at the time of its publication. Indeed, in January 1599, Henry had to visit the Parliament in person to accept the Edict passed. Religious tensions continued to affect politics for many years to come, though never to the aforementioned degree, and Henry 4 faced many attempts on his life; the last succeeding in May 1610.

Aftermath [edit]

Although the Edict of Nantes concluded the fighting during Henry IV's reign, the political freedoms information technology granted to the Huguenots (seen by detractors as "a land within the country") became an increasing source of trouble during the 17th century. The damage done to the Huguenots meant a pass up from x% to 8% of the French population.[76] The decision of King Louis XIII to reintroduce Catholicism in a portion of southwestern France prompted a Huguenot revolt. By the Peace of Montpellier in 1622, the fortified Protestant towns were reduced to two: La Rochelle and Montauban. Some other war followed, which concluded with the Siege of La Rochelle, in which imperial forces led by Cardinal Richelieu blockaded the city for fourteen months. Nether the 1629 Peace of La Rochelle, the brevets of the Edict (sections of the treaty that dealt with armed forces and pastoral clauses and were renewable by letters patent) were entirely withdrawn, though Protestants retained their prewar religious freedoms.

Over the remainder of Louis 13's reign, and especially during the minority of Louis XIV, the implementation of the Edict varied yr by year. In 1661 Louis Fourteen, who was particularly hostile to the Huguenots, started bold control of his government and began to disregard some of the provisions of the Edict.[77] In 1681, he instituted the policy of dragonnades, to intimidate Huguenot families to catechumen to Roman Catholicism or emigrate. Finally, in Oct 1685, Louis issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, which formally revoked the Edict and made the practice of Protestantism illegal in France. The revocation of the Edict had very damaging results for France.[77] While it did not prompt renewed religious warfare, many Protestants chose to leave France rather than catechumen, with most moving to the Kingdom of England, Brandenburg-Prussia, the Dutch Republic and Switzerland.

At the dawn of the 18th century, Protestants remained in significant numbers in the remote Cévennes region of the Massif Central. This population, known equally the Camisards, revolted against the authorities in 1702, leading to fighting that connected intermittently until 1715, afterwards which the Camisards were largely left in peace.

Chronology [edit]

Protestant engraving representing 'les dragonnades' in France under Louis 14.

- 17 Jan 1562: Edict of Saint-Germain, often called the "Edict of January"

- ane March 1562: Massacre of Vassy (Wassy)

- March 1562 – March 1563: First State of war, ended past the Edict of Amboise

- nineteen Dec 1562: Battle of Dreux

- September 1567 – March 1568: Second War, ended by the Peace of Longjumeau

- 10 Nov 1567: Battle of Saint Denis

- 1568–1570: Third War, ended past the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye

- March 1569: Battle of Jarnac

- June 1569: Boxing of La Roche-l'Abeille

- October 1569: Battle of Moncontour

- 1572: St. Bartholomew's Solar day Massacre

- June 1572: Death of Jeanne d'Albret

- 1572–1573: 4th War, ended by the Edict of Boulogne

- November 1572 – July 1573: Siege of La Rochelle

- May 1573: Henry d'Anjou elected King of Poland

- 1574: Death of Charles Nine

- 1574–1576: 5th State of war, ended by the Edict of Beaulieu

- 1576: Formation of the offset Catholic League in France

- 1576–1577: Sixth War, ended by the Treaty of Bergerac (too known as the "Edict of Poitiers")

- 1579–1580: Seventh War, ended by the Treaty of Fleix

- June 1584: Death of François, Duke of Anjou, heir presumptive

- December 1584: Treaty of Joinville

- 1585–1598: 8th State of war, ended by the Peace of Vervins and the Edict of Nantes

- October 1587: Battle of Coutras, Battle of Vimory

- Dec 1588: Assassination of the Knuckles of Guise and his blood brother

- Baronial 1589: Assassination of Henry Iii

- September 1589: Battle of Arques

- March 1590: Boxing of Ivry, Siege of Paris

- July 1593: Henry IV abjures Protestantism

- February 1594: Henry IV crowned in Chartres

- June 1595: Battle of Fontaine-Française

- April–September 1597: Siege of Amiens

- April 1598: Edict of Nantes issued by Henry Four

- October 1685: Edict of Fontainebleau issued by Louis 14

See likewise [edit]

- Edict of toleration

- List of wars and disasters past expiry cost

- Monarchomachs

- Religion in France

- Virtual Museum of Protestantism

- Siege of Paris (1590)

- Catholic League (French)

- Battle of Craon

References [edit]

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Knecht 2002, p. 91.

- ^ Lindberg, Carter (1996). The European Reformations. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 292.

- ^ McGrath, Alister (1995). The Intellectual Origins of the European Reformation. Massachusetts: Blackwell. pp. 39–43.

- ^ McGrath. The Intellectual Origins of the European Reformation. pp. 122–124.

- ^ Spickard, Paul; Cragg, Kevin (2005). A Global History of Christians: How Everyday Believers Experienced Their Earth. Grand Rapid: Baker. pp. 158–160.

- ^ a b Lindberg. The European Reformations. p. 275.

- ^ Cairns, Earl (1996). Christianity through the Centuries: A History of the Christian Church (third ed.). Grand Rapid: Zondervan. p. 308.

- ^ Grimm, Harold (1973). The Reformation Era 1500–1650 (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan. p. 54.

- ^ Grimm. The Reformation Era 1500–1650. p. 55.

- ^ Grimm. The Reformation Era 1500–1650. pp. 263–264.

- ^ Cairns, Earl. Christianity through the Centuries. p. 309.

- ^ a b Lindberg. The European Reformations. p. 279.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. ii

- ^ a b c d Knecht 1996, p. four.

- ^ a b Knecht 1996, p. 3.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 7.

- ^ Cottret, p. 101.

- ^ a b Knecht 1996, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Paul Bernstein, Robert W. Dark-green, History of Civilization, Vol.one, (Rowman & Littlefield, 1988), p. 328.

- ^ Holt, p. twenty.

- ^ a b Garnier, Edith, L'Alliance Impie Editions du Felin, 2008, Paris, p. ninety.

- ^ Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, (Pearson Educational activity Limited, 2012), p. 234.

- ^ Audisio, Gabriel, Les Vaudois: Histoire d'une dissidence XIIe – XVIe siecle,, (Fayard, Turin, 1998), pp. 270–271.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Knecht 1996, pp. half dozen–vii, 86–87.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. x.

- ^ Salmon, p. 118.

- ^ French republic : Renaissance, Religion and Recovery, 1494–1610, Martyn Rady. pp. 52–53. (1998)

- ^ Knecht, p. 195. (2007)

- ^ a b Knecht 1996, p. 25.

- ^ Salmon, pp.124–125; the cultural context is explored by N.M. Sutherland, "Calvinism and the conspiracy of Amboise", History 47 (1962:111–38).

- ^ Sutherland, North.M. (1984). Princes, Politics and Faith 1547-89. Hambledon Press. p. 64.

- ^ Salmon, p. 125.

- ^ Salmon, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 29.

- ^ Bryson, David (1999). Queen Jeanne and the Promised State. p. 111.

- ^ Frieda, Leone (2003). Catherine de Medici: Renaissance Queen of France (Start Harper Perennial edition 2006 ed.). Harper Perennial. pp. 132–149.

- ^ See fifty'Hôpital speech to the Estates Full general at Orléans of 1560.

- ^ a b c Knecht 1996, pp. xxx–31.

- ^ Michel de Castelnau, The Memoirs of the Reigns of Francis I and Charles IX (published in London, 1724 and reproduced past ECCO) p. 110.

- ^ Michel de Castelnau, The Memoirs of the Reigns of Francis II and Charles Nine, p. 112.

- ^ Knecht 2000, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Rev. James Fontaine and Ann Maury, Memoirs of a Huguenot Family (New York) 1853.

- ^ Albert Guérard, France: A Modern History, (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1959), 152.

- ^ a b c d e Knecht 1996, p. 35.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Sarah; Spicer, Andrew (2005). Defining the holy : sacred infinite in medieval and early modern Europe. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN0754651940. OCLC 60341480.

- ^ Knecht 2000, p. 86.

- ^ Trevor Dupuy, Brusque Johnson and David L. Bongard, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, (Castle Books: Edison, 1992), p. 98.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 37.

- ^ Frieda, 268; Sutherland, Ancien Régime, p. 20.

- ^ a b Knecht 1996, p. twoscore.

- ^ a b Jouanna, p. 181.

- ^ Knecht 2000, 151.

- ^ Jouanna, p. 182.

- ^ Jouanna, p. 184.

- ^ Jouanna, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Jouanna, 196.

- ^ Jouanna, p. 199.

- ^ Jouanna, p. 201.

- ^ Lincoln, Bruce, Discourse and the Construction of Society: Comparative Studies of Myth, Ritual, and Nomenclature, Oxford Academy Press United states, P98

- ^ Jouanna, p. 204.

- ^ Jouanna, p. 213.

- ^ Knecht 2000, p. 181.

- ^ Knecht 2000, p. 190.

- ^ Knecht 2000, p. 191.

- ^ Knecht 2000, p. 208.

- ^ a b c d Knecht 1996, p. 65.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 90.

- ^ a b Knecht 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 73.

- ^ Knecht 2000, p. 264.

- ^ a b Knecht 2000, p. 270.

- ^ Knecht 2000, p. 272.

- ^ Philip Benedict, 'Un roi, une loi, deux fois: Parameters for the History of Catholic–Protestant Co-existence in France, 1555–1685', in O. Grell & B. Scribner (eds), Tolerance and Intolerance in the European Reformation (1996), pp. 65–93.

- ^ Hans J. Hillerbrand, Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set, paragraphs "France" and "Huguenots"; Hans J. Hillerbrand, an skillful on the subject, in his Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set claims the Huguenot community reached as much as 10% of the French population on the eve of the St. Bartholomew'southward Day massacre, declining to 8% past the end of the 16th century, and further subsequently heavy persecution began once once again with the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV of France.

- ^ a b c "Edict of Nantes". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 5 April 2013.

Bibliography [edit]

- Acton, John (1906). . . New York: Macmillan. pp. 155–167.

- Baird, H. Thou. (1889). History of the Rise of the Huguenots of France. Vol. 1.

- ——— (1889). History of the Rise of the Huguenots of France. Vol. 2. New edition, two volumes, New York, 1907.

- Baird, H. K. (1895). The Huguenots and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. C. Scribner'southward sons.

- Benedict, Philip (1996). "Un roi, une loi, deux fois: Parameters for the History of Catholic-Protestant Co-existence in France, 1555–1685". In Grell, O. & Scribner, B. (eds.). Tolerance and Intolerance in the European Reformation. New York: Cambridge University Printing. pp. 65–93. ISBN0-521-49694-2.

- Di Bondeno, Agostino (2018). Colloqui di Poissy. Rome: Albatros. ISBN978-8-85679319-2.

- Castelnau, Michel de, The Memoirs of the Reigns of Francis Ii and Charles Nine (published in London in 1724 and reprinted past ECCO.)

- Cottret, Bernard (2000) [1995], Calvin: Biographie [Calvin: A Biography] (in French), Translated by One thousand. Wallace McDonald, M Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans, ISBN0-8028-3159-1

- De Caprariis, Vittorio (1959). Propaganda e pensiero politico in Francia durante le guerre di religione (1559–1572). Napoli: Società Editrice Italiana.

- Diefendorf, Barbara B. (1991). Beneath the Cross: Catholics and Huguenots in Sixteenth-Century Paris. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press. ISBN0-19-506554-9.

- Davis, Natalie Zemon (1975). Society and Culture in Early on Modern France. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN0-8047-0868-1.

- Frieda, Leonie (2005). Catherine de Medici. London: Phoenix. ISBN978-0-06-074492-2.

- Greengrass, Mark (1986). France in the Age of Henry IV . London: Longman. ISBN0-582-49251-3.

- ——— (1987). The French Reformation. London: Blackwell. ISBN0-631-14516-8.

- ——— (2007). Governing Passions: Peace and Reform in the French Kingdom, 1576–1585. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-nineteen-921490-vii.

- Guérard, Albert, France: A Modern History (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Academy of Michigan Press, 1959).

- Holt, Mack P. (2005). The French wars of religion, 1562–1629. Cambridge. ISBN0-521-83872-X.

- Hulme, East. M. (1914). The Renaissance, the Protestant Revolution, and the Catholic Reaction in Continental Europe. New York.

- Jouanna, Arlette; Boucher, Jacqueline; Biloghi, Dominique; Thiec, Guy (1998). Histoire et dictionnaire des Guerres de religion. Drove: Bouquins (in French). Paris: Laffont. ISBNtwo-221-07425-4.

- Knecht, Robert J. (1996). The French Wars of Organized religion 1559–1598. Seminar Studies in History (second ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN0-582-28533-X.

- ——— (2000). The French Ceremonious Wars. Modern Wars in Perspective. New York: Longman. ISBN0-582-09549-2.

- ——— (2001). The Rise and Fall of Renaissance French republic 1483–1610. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN0-631-22729-6.

- ——— (2002). The French Religious Wars 1562–1598. Osprey Publishing. ISBN9781841763958.

- ——— (2007). The Valois: Kings of France 1328–1589 (2nd ed.). New York: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN978-1-85285-522-2.

- Lindsay, T. M. (1906). A History of the Reformation. Vol. ane. T and T Clark.

- ——— (1907). A History of the Reformation. Vol. 2.

- Salmon, J. H. Yard. (1975). Society in Crisis: France in the Sixteenth Century. London: Methuen. ISBN0-416-73050-7.

- Pearson, Hesketh, Henry of Navarre: The Rex Who Dared (New York: Harper & Rowe, Publishers, 1963).

- Sutherland, North. Thousand. (1962). "Calvinism and the conspiracy of Amboise". History. 47 (160): 111–138. doi:x.1111/j.1468-229X.1962.tb01083.x.

- Sutherland, Northward. M. Catherine de Medici and the Ancien Régime. London: Historical Association, 1966. OCLC 1018933.

- Thompson, J. West. (1909). The Wars of Organized religion in France, 1559–1576. Chicago: Chicago, The University of Chicago Press; [etc., etc.

- Tilley, Arthur Augustus (1919). The French wars of religion.

Historiography [edit]

- Diefendorf, Barbara B. (2010). The Reformation and Wars of Religion in France: Oxford Bibliographies Online Enquiry Guide. Oxford U.P. ISBN9780199809295.

- Frisch, Andrea Forgetting Differences: Tragedy, Historiography, and the French Wars of Religion (Edinburgh University Printing, 2015). x + 176 pp. total text online' online review

- Christian Mühling: Die europäische Debatte über den Religionskrieg (1679–1714). Konfessionelle Memoria und internationale Politik im Zeitalter Ludwigs 14. (Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz, 250) Göttingen, Vandenhoeck&Ruprecht, ISBN 9783525310540, 2018.

Primary sources [edit]

- Potter, David L. (1997). French Wars of Faith, Selected Documents. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN9780312175450.

- Salmon, J.H.M., ed. French Wars of Organized religion, The How Important Were Religious Factors? (1967) brusque excerpts from primary and secondary sources

External links [edit]

- The Wars of Religion, Part I

- The Wars of Organized religion, Part II

- French Religious Wars Archived 17 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- The Wars of Religion Archived 16 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- The eight wars of faith (1562–1598) in The Virtual Museum of Protestantism

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Wars_of_Religion

0 Response to "what allowed the huguenots to worship freely in france"

Post a Comment